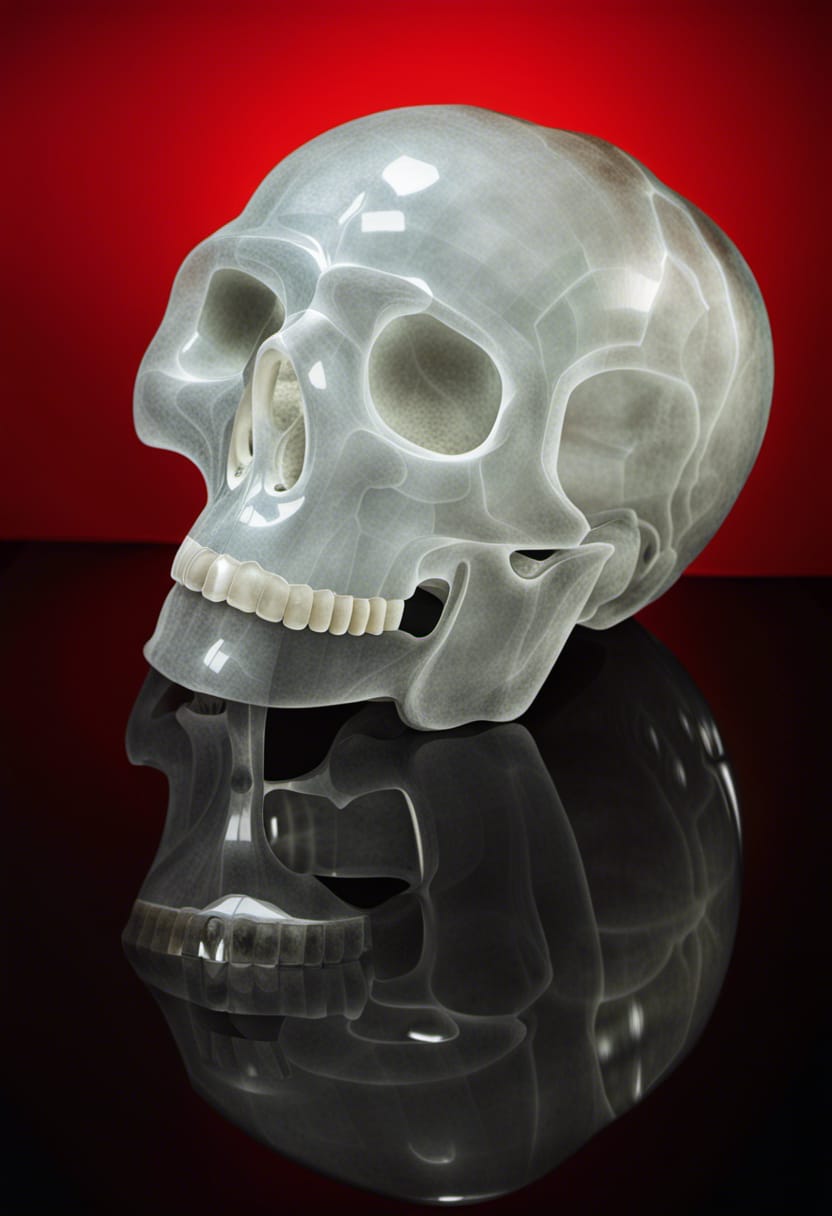

The Smithsonian Museum crystal skull is one of the most mysterious and controversial objects in the world. It is a human-sized skull carved from a single block of clear quartz, weighing about 31 pounds and measuring almost 10 inches high. It was donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1992 by an anonymous person who claimed it was of Aztec origin. However, scientific studies have shown that it is not an ancient artifact, but a modern fake, probably made in Mexico in the 20th century. Despite its dubious authenticity, the crystal skull has fascinated many people who believe it has supernatural powers and a connection to ancient civilizations.

The origin of the crystal skull is shrouded in mystery. The donor who sent it to the Smithsonian did not provide any information about where or how he acquired it. He only said that he bought it in Mexico in 1960. The Smithsonian's anthropologist Jane MacLaren Walsh, who has researched the skull extensively, believes that it was carved by a Mexican lapidary artist using modern tools and techniques. She also thinks that it was inspired by other crystal skulls that were popularized by adventurers and collectors in the 19th and 20th centuries.

One of the most famous crystal skulls is the one owned by Frederick Arthur Mitchell-Hedges, a British explorer who claimed to have found it in a Maya temple in Belize in the 1920s. His daughter, Anna, later said that it was the "Skull of Doom" and that it had magical properties, such as emitting light, making sounds, and healing diseases. However, Walsh and other scholars have debunked these claims and shown that Mitchell-Hedges actually bought his skull from an antique dealer in London in 1943. The dealer had acquired it from Eugene Boban, a Frenchman who had sold many crystal skulls to museums and collectors in Europe and America. Boban claimed that his skulls were of Aztec or Maya origin, but they were most likely made by modern artisans in Mexico or Europe.

Another famous crystal skull is the one displayed at the British Museum in London. It was donated by Tiffany and Co. in 1897, who had bought it from Boban as well. The British Museum also has a smaller crystal skull that was given by a collector named George Heye in 1933. Both skulls have been examined by experts who concluded that they were not pre-Columbian artifacts, but modern carvings made with rotary wheels and abrasives. The same conclusion was reached for another crystal skull at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, which was also sold by Boban to a collector named Alphonse Pinart in 1878.

The Smithsonian Museum crystal skull is similar to these other skulls in terms of size, shape, and material. It is also hollow, which is unusual for crystal skulls. Walsh and her colleague Margaret Sax have analyzed the skull using various methods, such as scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and optical microscopy. They found evidence of modern lapidary techniques, such as saw marks, polishing compounds, and abrasives. They also detected traces of water and sodium chloride inside the skull, which suggest that it was soaked in salt water to enhance its clarity. Based on these findings, they estimated that the skull was made sometime between 1950 and 1960.

The Smithsonian Museum crystal skull does not have any historical or archaeological value, but it does have a cultural and psychological significance. Many people are attracted to the skull because of its beauty, mystery, and symbolism. Some believe that it has metaphysical properties, such as enhancing intuition, psychic abilities, and spiritual awareness. Some also associate it with ancient legends and prophecies, such as the Maya calendar and the end of the world.

The Smithsonian Museum crystal skull is a product of human imagination and creativity. It reflects the fascination and curiosity that people have for the unknown and the mysterious. It also shows how myths and stories can be created and perpetuated by popular culture and media. The Smithsonian Museum crystal skull is not a genuine artifact from an ancient civilization, but it is a genuine artifact of human culture.

This section contains images and stories of my skulls based on my experiences. My perspectives are not meant to be the ultimate authority on crystal and stone skulls. They only reflect who I am as a person. Images shown of strange entities and forms within the skulls are projections of my mind.

Read More

A collection of information and suggestions about a portion of the better-known crystal skulls. Ignoring the age rating of contemporary, old, and ancient, there are skulls that are famous because they were pushed into the public’s eye. All crystal and stone skulls share wisdom and power, all possess ancient qualities because they consist of similar material.

Read More

A collection of external links to other websites that I find interesting. These websites are in no way affiliated with Crystal & Stone Skulls OPW and do not necessarily reflect my views. Likewise, the owners of these websites do not necessarily agree with my views.

Read More